The last three years have been the driest that the western United States has ever faced – and it’s likely to stay that way. Californians are under mandatory drought restrictions for the 2nd time in eight years, their lawns turning brown and their showers shorter. But for farmers throughout the Southwest, the situation is far more serious.

The Colorado River, a major water source for 40 million people in the region, is also beset by drought, threatening its ability to supply farmers and cities around the U.S. West. At the same time, more people are moving to western states like Nevada, as well as desert cities in California – putting further pressure on water systems. Climate change and population growth combined have caused a 50% reduction in the availability of freshwater per capita in these areas.

“You’ve got a growing population that also needs water for homes and people,” says Seth Siegel, author of “Let There Be Water: Israel’s Solution for a Water-Starved World.” “That’s a problem, and it creates a situation where agriculture in the area is at war with homeowners.”

In his book, Siegel wrote about a simple technology that uses gravity to drip irrigation onto fields that have previously been flooded with water. Later, he joined the company, N-Drip, as its chief sustainability officer.

Harnessing gravity

N-Drip is just one of several technologies already helping farmers carve out a future in a climate-changed West. Sensors for farmers, indoor growing operations, and even robot-controlled vertical farms are making strides in the food-growing industry.

Much of the world’s farms are still operating on 5,000-year-old technology: flooding fields to irrigate them, letting water flow down small trenches between rows of crops, waiting for it to evaporate, and then doing it again when the soil is dry. Globally, about 85% of all global agriculture that has irrigated fields uses this ancient method of flood irrigation, he says. “In a climate crisis situation where rain patterns are being disrupted – some places have too little water, others have too much water – this just doesn’t make sense.”

In the U.S. close to 40% of all irrigated fields are flood irrigated – which made sense 65 years ago when other techniques weren’t available. Then Israeli farmers started using pressurized drip irrigation, where water is forced through pipes or tubing directly onto plants. It works well, but requires clean water and quite a bit of energy to run the systems. It is also much more costly – between $1.50 to $4.50 per square foot – and wastes about 70% of the water.

Instead, the N-Drip system uses gravity – no pumps, filters, or energy – to deliver water to plants. Previously flooded fields have a slight slope to them, which the system monopolizes for irrigation. The company says it saves 50-70% of water using the method, reduces fertilizer use, and lowers carbon emissions by 80%. While this is a new technology, the company says it can scale to major farming enterprises. N-Drip is also much less expensive than traditional pressurized drip irrigation, a few hundred dollars for the parts and a few hundred more to install for an average farmer, Siegel says.

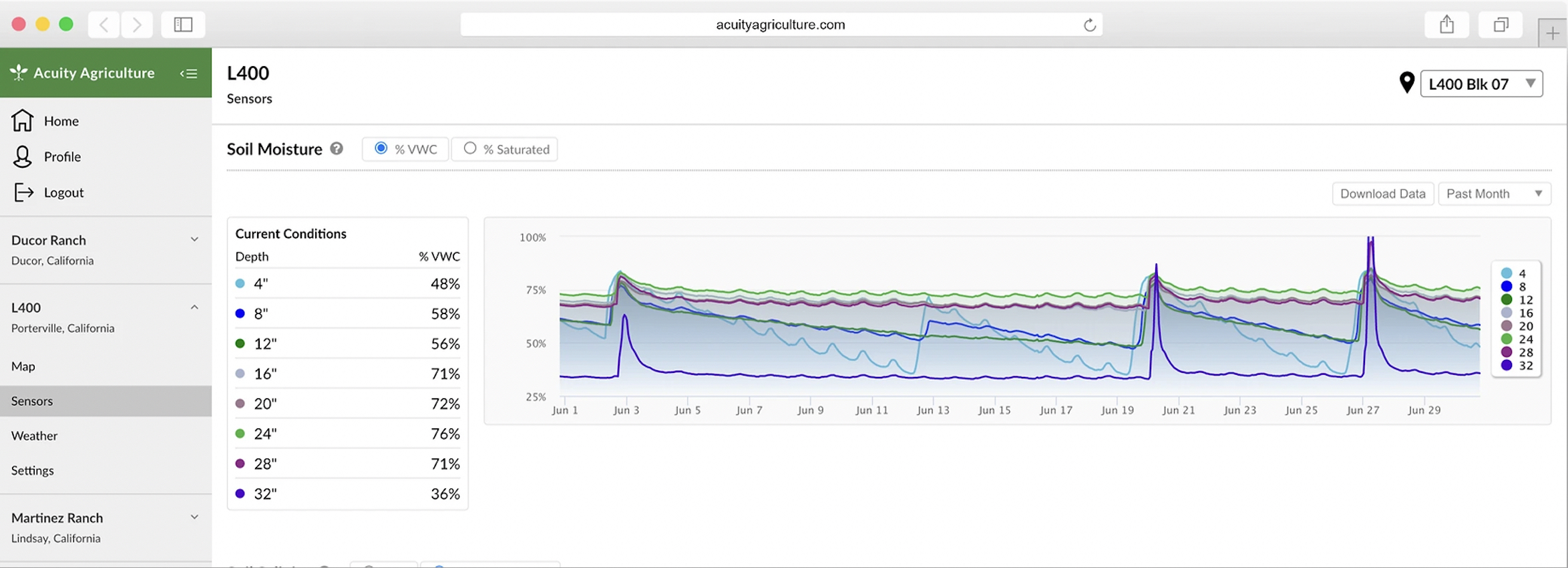

Other tech approaches try to reduce water by using data – giving farmers a view of what’s happening under the soil after water reaches plants. That’s what Acuity Agriculture hopes to offer. The company is creating a dashboard for farmers, bringing together soil, climate, and equipment data, a solution started by growers and engineers, says Megan Dilley, Acuity’s CEO. “The thing that makes us different is that we have a strong agriculture background: we were built to make farmers’ lives easier.”

The system combines hardware in the field with a dashboard that gives farmers information about soil moisture, irrigation, and how to optimize growth. Dilley explains that in California, farmers face big fines if they go over their regulated allotment of water – and Acuity helps them manage water properly so they don’t overuse. Farmers also have to send reports on their water use – which adds a lot of administrative time to a job that otherwise is in the field, and the dashboard can help them do that smoothly.

In the future, she sees the company becoming a “Quickbooks for water”- a fully-integrated software solution for farm management, with a focus on water and water resources.

Sensing moisture levels

Some people see the future of farming as moving indoors, where conditions and resources can be managed more closely. That’s the idea behind Pangaea Global Technologies, which creates lighting for large indoor greenhouses (cannabis is one crop, but there are many others.) While the initial costs of setting up an indoor farm are high, they are offset by the cost of tractors, combines, and other equipment required in traditional farms, says Bryan Fried, Pangaea’s CEO. Also, crops can be grown year-round in an indoor farm, so yields are higher – some studies show as much as six times higher.

In addition, indoor farming doesn’t suffer from cold snaps, heavy rains, insects, or plant diseases. “This results in a more secure and dependable supply chain which is good for business viability and allows the farmer to be more financially secure,” says Fried. “Many large grocers such as Walmart have already pivoted to indoor farms for such staples as leafy greens, peppers, strawberries, and tomatoes.” There are already 40,000 indoor farms operating across the country. That includes Infinite Acres, a vertical farm and a grow house, which can produce 5 million salad servings a year from just one of its facilities.

When it comes to water use, indoor farms leverage managed systems called fertigation, combining fertilizer and water monitored and controlled by software. Sensors detect soil moisture content, nutrient levels, and other factors that contribute to growth. Water is recycled, and plants receive a precise amount based on the grower’s recipe, according to Fried. Indoor farms of this type have demonstrated a reduction in water usage by as much as 95%.

Less stress on the environment

Another approach to indoor farming is fitting the crops into a small footprint and growing in tall skinny buildings, known as vertical farming. That’s what Avondale, Arizona-based OnePointOne is working on. Without dependence on climate or weather, vertical farms can produce in places previously unable to support traditional forms of farming. They can also grow more in less space, reducing the impact on the environment by using less land and fewer natural resources.

“The macro benefit of vertical farming is that the global production of plants will become a sustainable effort, unleashing the power of plants on human health without harming environmental health,” says Samuel Bertram, CEO, and co-founder of OnePointOne and Willo Farm, which sells leafy greens and berries from a vertical farm direct to consumers.

He adds that the system uses 99% less water than traditional farming because it uses aeroponics: a nutrient-packed mist with no soil and small amounts of water. Artificial intelligence can adjust watering systems and maximize plant health. OnePointOne says it goes beyond organic, with plants grown in a completely controlled environment, free of pollutants, devoid of pests, and with minimal human interaction.

“Each plant is grown in the most optimal controlled conditions that make it possible to avoid the use of any synthetic or organic pesticides,” says Bertram.

The future of food in the American West will depend on solutions that offset shrinking amounts of water against a growing population. Technology will be a key factor in making the system work. N-Drip’s Siegel says that while farmers are traditionally reluctant to adopt new technology, the environmental conditions are changing fast enough to encourage action quickly.

Water in the West will always be a challenge, but with new approaches, farmers and people in cities alike may be able to continue their work, and appear eager to do, says Siegel. “We have interest almost every day from people in water scarce places,” he says.