For all its potential to help heal the earth, unfortunately, recycling is broken. One of the biggest bottlenecks in the system happens in a place most of us don’t spend much time thinking about: The recycling and reclaiming center.

Every year we generate billions of tons of waste, and only a very small percentage is recycled. Just 6% of the 40 million tons of plastic waste made it through the recycling process in the U.S. in 2021. Our current system faces numerous challenges, including the fact that recycling centers don’t have the proper technology to sort materials that are recyclable from those that are not. According to a recent Greenpeace report, plastic is “virtually impossible to sort for recycling.”

And if that plastic can’t be sorted, it can’t be recycled.

For P&G, “impossible” is just a good challenge. The company has ambitious ESG goals that require that 100% of the company’s consumer packaging will be designed to be recyclable or reusable.

Enter Holy Grail 2.0. This P&G collaborative project has been in development since 2016, and focuses on improving efficiency in the recycling process by embedding a unique digital watermark onto each product. This watermark is around the size of a postage stamp and applied directly on the packaging’s label or embossed into the plastic itself. Invisible to the eye, the mark can be detected by high-resolution cameras which will allow for better tracking and sorting of plastic packaging, making it easier to identify which materials are recyclable and which are not. The joint project is a significant part of P&G’s ESG goals around climate and waste.

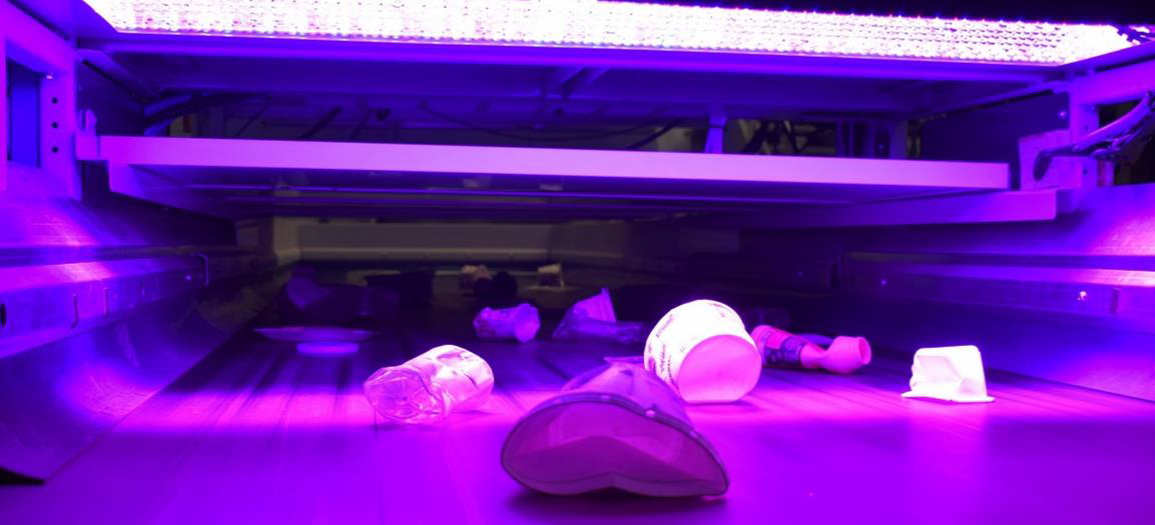

Recycling through the Holy Grail scanner Credit: AIM/European Brands Association

Sorting out the problem

Gian De Belder founded the Holy Grail program in 2016 out of a personal frustration with the way sorting systems worked. “I basically found out that a lot of our packaging wasn’t going in the right direction,” says De Belder, Procter & Gamble’s technical director for the company’s R&D Packaging Sustainability group. That’s when he discovered that even if we’ve dropped our used packaging into the right bin, those materials won’t get back into the system unless they’ve been properly sorted and processed.

“If we can crack this bottleneck then obviously we do have much more [effective recycling] and higher recycling rates in general,” he says.

It’s not quite as easy as it sounds. “One big problem is deciphering between the different types of plastic,” says Rachel Zipperian, who leads sustainability and citizenship at P&G. “If you have polypropylene or if you have polyethylene, they have to be separated before they can go to different reclaimers, and different recycling processes.”

When this process fails, our waste isn’t being recycled, or at least not in the most efficient and environmentally responsible way it could be.

The other significant challenge is that recycling centers operate independently with different standards and technologies. “Some places are more invested in technology than others. There are optical sorters and other different things that exist, but [digital watermarking] is a way to get the sorting done in a more precise way,” she says.

A concept of the Holy Grail digital watermarking Credit: AIM/European Brands Association

Making the sorting process more uniform will require systemic change, says De Belder. What we’ve been doing for the last 30 to 50 years no longer works. “In general, the waste industry is still very analog. It’s not really digitalized at all. And that’s the key.”

How digital watermarking works

Digital watermarks are unique digital identifiers for plastics and other recyclables that can be as small as a postage stamp and are embedded in the design of the packaging. The watermark contains information about the type of plastic used in the packaging, as well as any other relevant data that can help with the sorting process. These watermarks are like QR codes that allow the materials to be tracked throughout the entire recycling process by a camera-based sorting system. Cameras and other sorting devices can then be programmed to pick up these watermarks to sort waste correctly and simplify the process.

Essentially, these digital watermarks are there to tell us a story—what the product is made of, whether it’s plastic or some other material. If it is plastic, what kind of plastic? What kind of colorants does it contain? Can items with these colorants be recycled or not? And can they be recycled with other recyclable materials or do they need to be separated? If all this information were contained in a digital watermark that could be read by a sensor at a sorting center, the results would eventually lead to higher recycling rates.

“If nothing happens in terms of digitalization of the waste industry, the best estimate in terms of recycling rates for household packaging is that we’re going to reach 45% by 2030,” De Belder warns. But, he argues, the successful implementation of digital watermarking could increase that number by a factor of 10-14 percentage points.

How’s it going?

As the world continues to face growing environmental challenges, it’s becoming increasingly important to find innovative solutions to these problems, and digital watermarking is one such solution that has the potential to make a real difference in the fight against waste and pollution. But it’s a long road.

At the end of 2021 Holy Grail 2.0 had developed a functional prototype able to detect and separate packaging from packaging waste and allowed for category-specific sorting. By the end of 2022, the prototype was tested for speed, accuracy, and detection efficiency.

The project is currently in its third phase which involves deploying the prototype in a large-scale pilot in a commercial sorting or recycling facility, first in France and then later in Germany. In this phase, consumers will be able to buy on-shelf products with digitally watermarked packaging, which will enter the waste stream after consumption. The plan is to go live with this project within the calendar year 2024.

A joint effort

In order for the project to be successful, all companies need to be committed to using digital watermarking on packaging. While the cost for a manufacturer to be part of the Holy Grail 2.0 project is not publicly disclosed, it has been a collaborative effort from the start, involving P&G,, recycling industry stakeholders, research organizations, and other consumer goods companies, including Nestle, PepsiCo, and Unilever.

“Collaboration is key,” says Tracey Long, Director of Scientific Communications at P&G. She acknowledges the challenges in partnering with all the various stakeholders across the value chain, but also acknowledges the necessity of the project to fix our broken recycling system. “That’s the critical difference on this one,” she says. “This is not something that we do just for us…It’s a team sport.”